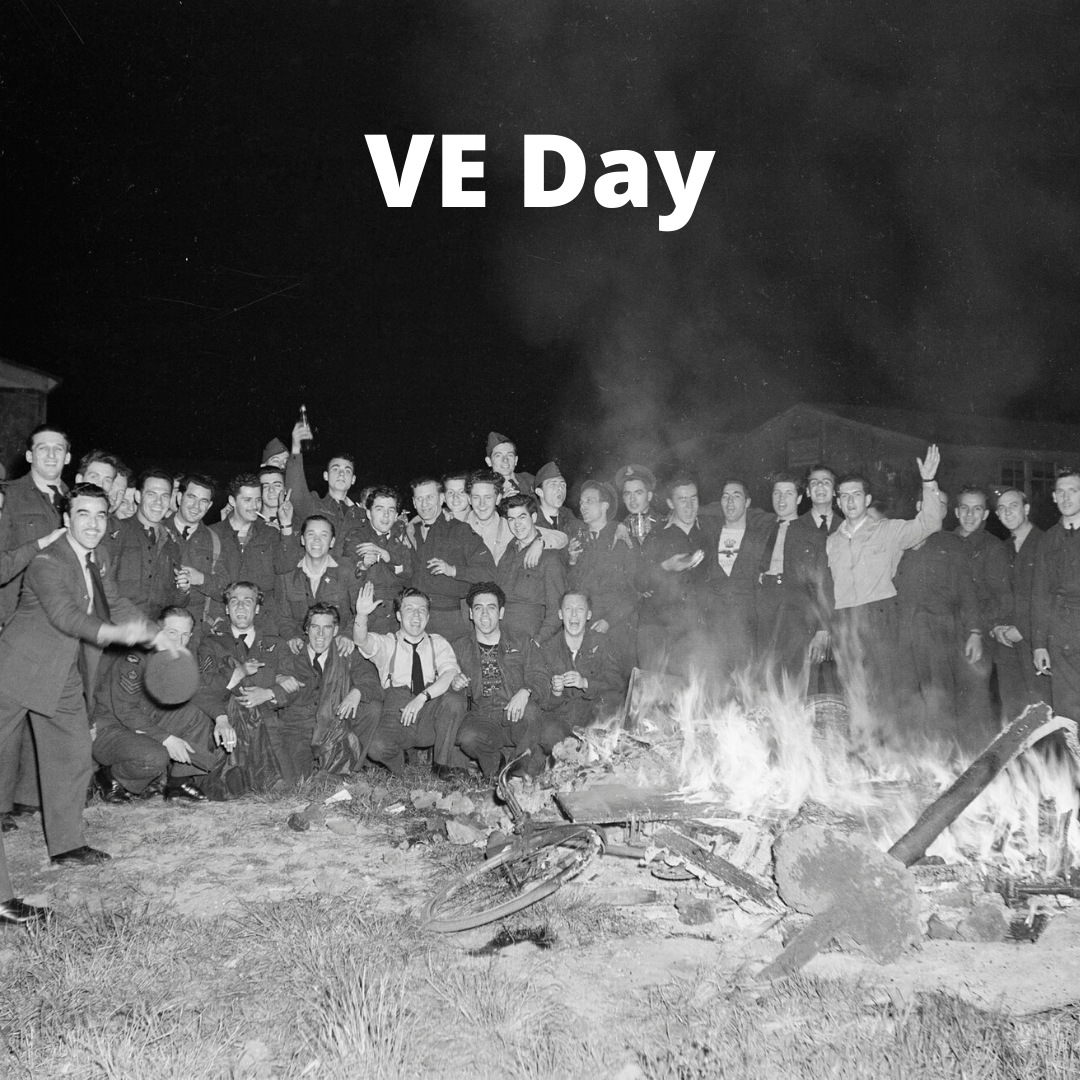

Victory in Europe Day (VE Day)

May 8, 1945 – millions of people across the globe celebrated the surrender of Germany and the end of the Second World War in Europe. VE Day, as it was named, was marked with parades, dances, religious ceremonies, and in the case of Halifax, Nova Scotia, riots and looting. Germany’s surrender did not come as a surprise to the Allies. With Berlin surrounded, Adolf Hitler had committed suicide on April 30, naming Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz as his successor. Dönitz negotiated and signed Germany’s unconditional surrender one week later.

Victory over Japan Day (VJ Day)

The Potsdam Declaration, issued by Allied leaders on July 26, 1945, called on Japan to surrender. Japan refused, and subsequently the controversial decision was made to drop the atomic bombs on Japan that had been developed in the United States by the Manhattan Project. On August 6, 1945 the United States dropped a 13 kiloton atomic bomb known as “Little Boy” on the city of Hiroshima, Japan. Three days later, a 21 kiloton atomic bomb nicknamed “Fat Man” was dropped on Nagasaki, Japan.

Fearful of further devastating bombings, the Japanese surrendered unconditionally on August 14, 1945. August 15 was celebrated as Victory over Japan Day (VJ Day) throughout North America and Europe. The official Japanese surrender was signed on September 2, effectively ending the Second World War.

The War Comes to a Close

The cost of victory was high, however. It is estimated that worldwide the war cost $1.72 trillion (CAD); $24 trillion (CAD) today with inflation. Casualty rates were also the highest of any conflict, then or since, with an estimated 20-25 million military casualties and 40-55 million civilian casualties.

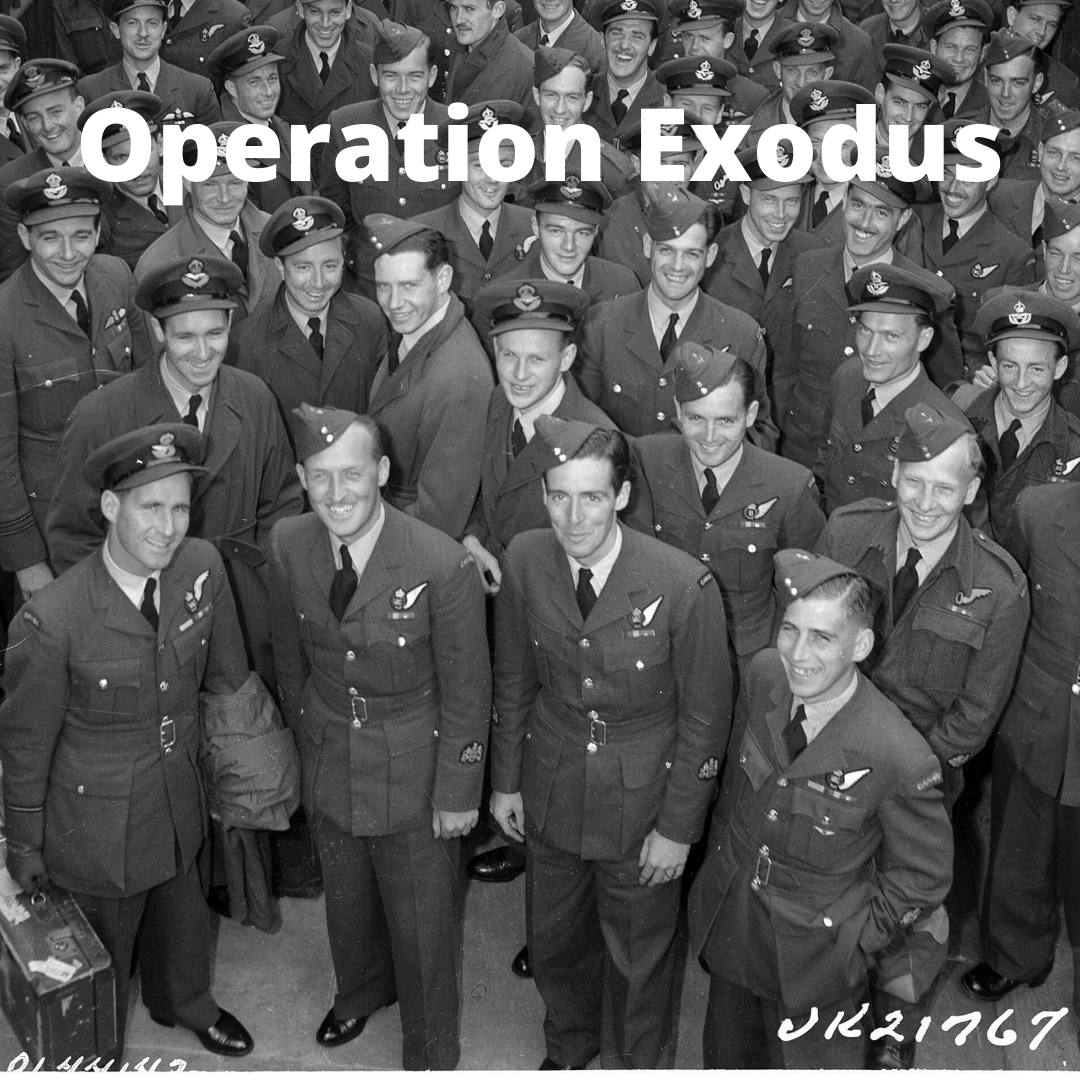

Following VE and VJ Days, RCAF transport and bomber squadrons played an important role in transporting freight, mail, and personnel around Europe. The RCAF was also tasked with returning personnel to England who had been held as Prisoners of War (POWs) in Germany and the Pacific.

As conditions in Europe settled, the RCAF’s commitments were gradually reduced, and demobilization began. Many squadrons were disbanded and Air Force personnel were released from service and returned home. This was a slow, and at times frustrating, process for the Canadian-bound personnel, as the wait times to get home extended well into 1946. By March 1946 the RCAF force had shrunk from over 215,000 at its peak to just over 30,000 personnel, with an ultimate goal of reducing the Regular Force down to just 16,100. Equipment also needed to be demobilized, and excess aircraft were sold, recycled, or even burned, as the RCAF transitioned into its smaller, peace-time role.